Memories in Clay

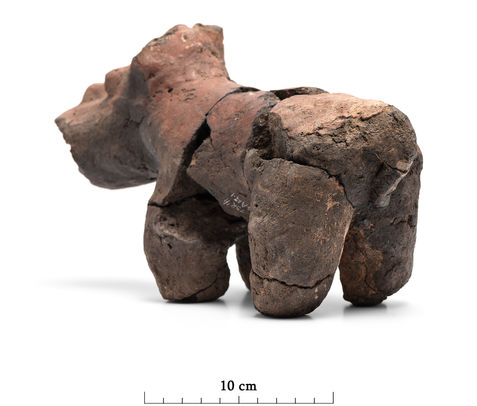

Ancient clay figurines from Schroda — an Iron Age site near the confluence of the Limpopo and Shashe rivers, South Africa. ca. 900 AD.

Museum Photography and Interpretation

To learn more about southern Africa’s unwritten past archaeologists endeavour to find and study the remnants of ancient societies. These are often the objects and fragments of ancient village life that are left behind and lie buried in the earth for untold years awaiting their chance to serve as distant memories of lives once lived. The collection of millennium-old clay figurines recovered from archaeological excavations at Schroda provides an opportunity to visually explore some aspects of Iron Age society through objects of embodied craftsmanship and symbolic expression.

AD 900

At the base of a rocky outcrop overlooking the Limpopo River to the north lies the ancient settlement known to archaeologists as Schroda. Buried in the soil are the traces of an Iron Age society that once made this plateau their home. Several excavations have uncovered numerous stone features and structures along with trade goods such as ostrich eggshell beads, ivory, and glass beads from the Middle East. In addition, many bone tools, copper ornaments, iron farming implements, and fragments of clay pottery were recovered from across the site. The wealth of material recovered from Schroda suggests a vibrant community that was an economic and social hub for the elephant hunters and cattle herders of the region. Among the objects recovered from this thriving society are a remarkable collection of earthenware figurines.

Clay figurines are not uncommon in archaeology, but the concentration found at Schroda is remarkable. Some were scattered evenly across the site, while others appeared in buried clusters — the latter seemingly broken before being discarded. Their presence on site, along with the varied contexts from which these objects were recovered, raises questions about the function and significance of art, and in particular sculpture, in this society over 1,000 years ago.

The context in which they were found, along with their subject matter and form, offers clues, but a full understanding would require access to the belief systems and worldview of the time. These more intangible aspects of Schroda’s past lie beyond the reach of excavation. Still, certain symbols endure, resonating across time through our shared human experience.

The female form is recognised in several figurines, all rendered in a shared abstract style. Interestingly, each was recovered from areas identified as private homesteads. Shown below is the most complete example in this style.

From the front, the figurine presents a conical, phallic-like form, stylised with legs (one fractured), a navel, breasts, and symmetrical side protrusions. A shallow hole visible on the front may have been used to suspend the figurine, or perhaps remains as a trace of an attached adornment.

Rhythmic impressions across the surface enhance the tactile quality of the sculpture, accentuating the motif against the smooth expanse of the torso. These markings likely reference scarification or tattooing practices.

Symmetry is highlighted by the rounded breast shapes, reinforcing the figure’s female form.

The motif guides the gaze down the torso to the prominent navel, which it encircles.

The navel, both exaggerated and encircled, becomes the focal point of the sculpture. The motif offers a tactile experience, drawing rhythmic attention to the elongated torso while also decorating its phallic reading. From the side view, a compelling outward tension and compositional interplay emerges between the buttocks and the projecting navel. The breasts echo this dynamic but, due to their subdued form and size, do not mirror the same outward posture.

The navel can be read as a scar — a mark of detachment from the womb. It signifies a period of transformation, from conception to birth, and speaks to the reproductive process. Its protrusion from the phallic torso suggests both male and female systems are referenced, offering a harmonised reading of reproduction. While the breasts indicate a female form, their modest scale does not imply a nurturing role. Instead, the sculpture appears to capture a transitional phase — one that bridges the transition from childhood to adolescence.

This piece may encapsulate a liminal moment in the human experience. Its excavation from a domestic context suggests it could have been a personal possession. The presence of several similar sculptures points to shared cultural values and structured ways of approaching such life transitions — perhaps akin to what some today refer to as "the talk." Though the finer details of that cultural narrative may be lost, the figurine continues to speak — its message shaped in clay and fired through time, carrying traces of lesson, ritual, and human continuity.

From the side view, a striking outward tension and interplay is seen between the buttocks

and the exaggerated navel.

The figurines that follow form part of the broader collection excavated at Schroda. Unlike the above specimen, these sculptures were found in areas associated with both public and private activity, distinct from the domestic homestead context. The figurines represent depictions of wild animals, semi-humans (anthropomorphs) and domesticate animals.

Among the collection represented here, most figurines have been reassembled as they were broken and fragmented before burial or discard. Among the subjects depicted are an elephant, giraffe, hippo, birds, sheep, and cattle. The domesticate animals are notably smaller and appear intact, which may be due to their scale or differences in clay or firing technique or another reason. Most of the figures adopt a frontal, passive pose, although the elephant breaks this pattern with a more dynamic stance. Some figurines were made with moulded bases, suggesting they may have been designed to be moved, held, or positioned alongside other sculptures during specific activities or performances. Traces of pigment also indicate that several were once painted, adding another sensory dimension to how they may have been seen and used.

Such details — mobility, surface colour, selective fragmentation — may point to how these figurines were engaged with, perhaps in acts of storytelling, instruction, or ritual. These clay forms appear to have played a role in how knowledge, beliefs or values were shared. Each one offers a quiet lesson — not just in form and material, but in the ways people once made sense of the world around them.

The figurines were photographed on location at the Ditsong National Museum of Cultural History. A consistent white background and controlled lighting were deliberate choices to keep the focus on the objects themselves — their form, texture and colour. Showing each piece under the same conditions avoids distractions that can come from dramatic lighting or styled backgrounds, making it easier to compare objects across the collection. Importantly, the shadows cast by each figurine carry visual information we intuitively understand — they help us read shape, depth and surface, even when we’re not aware of it. This approach is both practical and respectful to the work of museum photography: it invites close, clear observation, allowing the subject to speak for itself.

While meaning may shift with time and memory, the artwork often endures. In viewing these objects from a future reality far removed from their (or their makers') context, we invite the past into the present that it may enrich our perspective on the world that we, and so many before us, inhabit.

A large assortment of the figurines is housed and on display at the

Ditsong National Museum of Cultural History.

Pretoria, South Africa.

Bibliography

Antonites, A.R., 2018. A revised chronology for the Zhizo and Leokwe horizons at Schroda. Southern African Humanities 31, 223–246.

Dederen, J.-M., 2021. E. Matenga, Archaeological Figurines from Zimbabwe; J.A. van Schalkwyk and E.O.M. Hanisch, Sculptured in Clay: Iron Age Figurines from Schroda, Limpopo Province, South Africa: “Figure-ing” it Out. HASA 54.

Dederen, J.-M., 2010. Women’s Power, 1000 A.D.: Figurine Art and Gender Politics in Prehistoric Southern Africa. NJAS 19, 20. https://doi.org/10.53228/njas.v19i1.212

Dederen, J.-M., Mokakabye, J., 2018. Of pools and birds : Celebrating motherhood in the first millennium. Nordic journal of African studies 27.

Dederen, J.-M., Mokakabye, J., 2017. Some Interpretive Notes on a Schroda Figurine Type.The South African Archaeological Bulletin 72, 171–174.

Hanisch, E.O.M., 1980. Of Certain Iron Age Sites in the Limpopo/Shashi Valley. University of Pretoria, Pretoria.

Hanisch, E.O.M., Van Schalkwyk, J.A., National Cultural History and Open-air Museum, 2002. Sculptured in clay: Iron Age figurines from Schroda, Limpopo Province, South Africa. National Cultural History Museum, Pretoria.

Huffman, T., 2012. Ritual Space in Pre-Colonial Farming Societies in Southern Africa. Ethnoarchaeology 4, 119–146. https://doi.org/10.1179/eth.2012.4.2.119

Humphreys, A.J., 2023. Anthropomorphic clay figurines from Early and Middle Iron Age sites in South Africa. University of South Africa, Pretoria.

Matenga, E., 1993. Archaeological figurines from Zimbabwe. Societas archaeologica Upsaliensis : Dept. of Archaeology [Institutionen för arkeologi], Univ. [distributör] ; Queen Victoria Museum, Uppsala : Harare.